Yesterday, I met with one of local daisy/brownie/scout troups. We had 8 little girls and their mothers. It was a lot of fun, and really brought back memories. The first time I ever talked about dolls and their history was at my girl scout troup when I was nine. My mother helped me write a little talk and description of each doll. We had just come from Europe, so I had a lot of fascinating examples, and some other special dolls,like my first Frozen Charlotte, a Swedish Tomte, a Shirley Temple look-alike-that was similar to my mother's beloved doll we had refurbished, the china head Aunt Rose made me for Christmas, and a gorgous Furga. Many years later, here I was again, with a few of the same dolls, and my "little talk" neatly typed out the way my mother showed me. I didn't have the heart to tell them that Frozen Charlotte in the poem froze to death; I told them she got very cold because she didn't wear a cloak.

Below are a few more excerpts from my book on Metal Dolls:

Chapter 6

Dolls with Metal Parts

Perhaps by making parts rather than the whole doll, inventors mitigated threats to their masculine identity as producers of feminine and frivolous objects. The evidence is inadequate to draw a definite conclusion as to why, but their products suggest that they felt more at ease with producing parts of women's bodies than with intact wholes. . . the leg joints on some dolls were placed over the thigh in such a way as to give the pubic region a male "anatomy"

Miriam Formanek-Brunell

Made to Play House: Dolls

and the Commercialization of

American Girlhood 1830-1930

If one accepts the above proposition wholeheartedly, male doll makers were literally creating dolls in their own image, and even so called-sexless or female dolls were meant to be male. There is something downright gruesome in the explanation given above for the networking and cottage industry involved in making dolls. While it is true that dolls were assembled this way, it is also true that there were equally important female manufacturers and doll makers in Europe who made dolls and doll parts. The fact that so many were mass-produced indicates as much an attempt to keep up with a growing demand that homemade cottage industries could no longer provide, as an obsession with feminine parts and a male desire to control their production. In any case, metal was becoming recognized as a durable and strong material for dolls by the end of the nineteenth century. As a result, there are many dolls made of all kinds of materials that have metal parts. The most common, perhaps, are the foreign costume dolls often sold to tourists. These are often made over a wire armature by wrapping strips of cloth or tape around the wire. One such pair of cloth dolls is Swedish. They date from around 1660. The dolls' heads are made of iron wire covered with silk-stuffed cloth. Their original clothes include metal lace underskirts and silk dresses with lead straps (Coleman II 258). They are on display in the Nordiska Museet, Stockholm. These dolls are very small, measuring only 3 inches to 3 and one-half inches in height.

Modern Greek Costume dolls also employ the wire armature method in their construction. The author has several in her collection made this way. The hands and forearms of the dolls are plastic or cloth. The upper arms are covered with clothing, and are usually just a piece of wire. The heads are wood or plastic masks covered with cloth. The features are painted and the dolls wear wigs of mohair or embroidery floss. The body is padded with strips of cloth. The legs, like the arms, are only partially covered. Dolls from Spain, India, Brazil, and Guatemala are also made in this way. Many craft books also give instructions about how to make this type of doll from pipe-stem cleaners or wire. Several types of dolls also have eyes made of metal or tin. One unusual head is made of ivory. A black, tapered spot is painted on top of her head. The body is wire and fabric with ivory lower limbs. The doll stands seven inches high and wears a petticoat of eighteenth century silk and gold embroidery (King ATAD 24). Another ivory doll is from the Bering Straits and has tin eyes (White, World 11). One doll from ancient Peru is of carved wood with metal eyes and teeth. The doll is two-dimensional with a flat back (39).

Wire-eyed dolls were popular in around 1825. In More About Dolls, Johl describes how these dolls work:

A wire from the upper hip passed through the body of this doll connected with the back of two blocks of wood on which the eyes were mounted. When the wire is pulled downward, the eyes open. When the wire is raised, the eyes closes. In some dolls the wire protrudes from the right side of the doll head just under the wig. When turned either to the left or to the right, the eyes open and shut." (Johl MAD 24)

A similar doll from around 1800 has a carton head and torso with arms made of wire. The wig was meant to be nailed on and the features are molded and painted (Coleman II 260). Wax dolls also had eyes that opened and closed by means of the wire mechanism Johl describes (Johl MAD 89). As Formanek-Brunell indicates, various manufacturers produced the mechanisms for eye and head movement. These included Dominico Checkeni, Fritz Bartenstein, and Rudolph M. Hunter (n.15 199).

Another type of wax doll had its head connected to its body by means of a metal spring. This doll is sixteen inches tall and dates from 1850. A Limbach bisque head has wire springs in its upper arms and legs. This doll has stationary glass eyes and a closed mouth. The torso and lower legs are of wood, and the head is attached by means of a dowel. The doll is seven and one-half inches tall (Coleman II 720). The company that made this doll, Limbach Porzellanfabrik,in Alsbach, Thür., Germany, started in 1772 and went out of business after 1927 (720). While many of the dolls had porcelain heads, metal was integral in putting them together. Limbach, apparently, was trying to strive for the ultimate realism by combining the delicate, realistic look that porcelain could give to a doll's face with the flexibility that the wire springs gave its body. A doll that had such a beautiful, naturally tinted face could now also be posed in life-like positions.

Other dolls could be posed in life-like positions, not because of wire springs, but because of metal parts in their ball jointed wood or composition bodies. Indeed, the so-called Springfield wooden dolls of Joel Ellis and of Martin also have spring joints and often sport pewter hands and feet as well. Ellis invented other things besides dolls. At nineteen, he designed a steam shovel for railroad excavating (Green Mountain Doll Club 24). In 1856, Ellis opened a wood working shop that specialized in baby and doll carriages. Because of this specialty, he was nicknamed "Cab" Ellis. The carriages were his most successful product and were even exported to Australia (24). It was Ellis's partners, three men named Britten, Eaton, and Brown, who first wanted to make dolls. The partnership held off, however, because the lathe and equipment necessary for this venture were too expensive (24). Then, in 1873, Ellis himself invented the tenon and mortise joints used on his dolls (White, World, 231). Ellis took out a patent to make the wooden dolls on May 20, 1873, setting up a separate company called The Cooperative Manufacturing Company (Green Mountain Doll Club 24-25). Ellis employed sixty people in his doll making venture. The dolls' joints were pinned with a steel pin. The body, head and upper limbs of the doll were kiln dried rock maple (25). The hands and feet of the doll were cast iron (25). The author has a doll very similar to Ellis's in her collection, but the lower limbs are missing. Supposedly, they were lost in the Great Chicago Fire, but this puts the dolls two years earlier than Ellis's. Perhaps Ellis had some other model in mind as inspiration when he made his first doll, just as Ruth Handler, creator of Barbie, had Bild's Lili in mind. Miriam Formanek-Brunell implies that the Ellis dolls and other Springfield dolls were created to be durable and serviceable according to masculine concepts of what a doll should be. She writes that Ellis and others concentrated on "joints and hinges" and "sacrificed anatomical realism to the mechanics of mobility" in their dolls (44). She also states that the pubic areas of the dolls, where the legs meet the hip joints, unconsciously, perhaps, resemble male, not female, anatomy (43). Were Ellis, Martin and Taylor, and the other Springfield doll makers playing God in Frankenstein fashion and attempting, at least subconsciously, to create dolls in their own masculine image? Since they were relatively silent on this point, we can only speculate.

The dolls of Albert Schoenhut, carefully sculpted in wood, had steel springs, as do many of the jointed composition bodies of the French and German bisque headed dolls of the nineteenth century. Schoenhut came to the United States from Germany in 1866 (Fromanek-Brunell 37). Schoenhut and other doll manufacturers arrived in this country at a time when Fromanek-Brunell writes that one third of the 3.3 million immigrants were German. Because Schoenhut had business acumen when he arrived, he and the others like him who emigrated "found places for themselves in a male world in which established German immigrant businessmen provided salaried employment (Fromanek-Brunell 37). Fromanek-Brunell writes that These German businessmen were successful in part because those there before them shared gender, class, and ethnicity, and were willing to help others like them (37). After working for another firm that made rocking horses, Schoenhut soon struck out on his own and made the wooden dolls and toys with metal parts that are now collector's items.

Not only dolls made of hard substances employ metal in their make-up, however. Even some cloth dolls have metal parts. On September 25, 1883, one Martha Wellington took out a patent for a cloth doll built on a wire framework. The material she used was stockinette over padded wire. The features were painted. The patent was No. 285, 448 (Spinning Wheel 19). Even female American manufacturers used hard substances because they were interested in durability. Sarah Robertson took out a patent for a cloth doll with joints that were made of metal buttons or wafers. Using these joints was supposed to keep the fabric from wearing out when the doll was sitting. China or bisque heads would then be attached to the Robertson bodies. The patent is dated August 21, 1883, No. 283, 513 (19).

Many of the French fashion dolls had metal parts or metal bodies. One lovely Huret doll has realistic metal hands. (Huret metal heads are discussed in more detail in Chapter Five). The doll is eighteen and one-half inches high and is marked "HURET 168 RUE DE LA BOETIE" (Knopf 191). The doll has a white bisque head with a hauntingly beautiful expression. Her wooden body is jointed at the waist so that she may sit. Her wig is auburn, her dress beige silk (191). The metal heads that Huret used were made by the following companies: The Jointed Doll Company, The Co-operative Doll Company, and The New England Doll Company. Huret apparently experimented with several materials. At one point, Jean Lotz mentions on her Internet Wood Doll Gallery that Huret made a doll with a wooden head, featured in the magazine Doll News in 1963. Lotz refers to Huret's business as a "Fancy Doll Studio." Also dolls marked "P and D" have metal hands. The letters could stand for Petit and Dumontier, who made bisque headed dolls (Coleman II 441). Mlle. Huret also made metal bodies. One of these has socket joints at the shoulders, elbows, wrists, waist, hips and knees (Tarnowska 127).

Mlle. Huret, however, was not the only manufacturer to make an all-metal doll body. Maison Rohmer, a company that made dolls from about 1856-1879, also made a doll with a metal body according to a patent by one of her relatives, Reidmeister. Marie Léontine Rohmer was born January 13, 1829 in Strasbourg. She was the daughter of a physician, but at 27, she chose another career, that of doll maker. In fact, it is unlikely that she could have pursued her father's calling, medicine, as a woman living in the heart of the nineteenth century. Yet, at twenty seven, she opened a doll factory in Paris, according to Anne Marie Porot in her article "The Rohmer Dolls" (108). Even today, hers was a remarkable achievement. Mlle. Rohmer was scrupulous for several years after she opened her factory to take out patents to protect her creations.

By 1859, Mlle. Rohmer had become Mme. Vuillaume by marrying a civil engineer. Her sister married Reidmeister, the other doll maker in the family. Together, they survived an embarrassing adventure in the French courts that involved Mlle. Huret and her dolls. Mme. Porot writes that "in this period of 1860-61...she found herself in the painful position of a lawsuit by Mademoiselle Huret for counterfeiting" (108). Mme. Vuillaume had begun making a doll with metal parts according to her brother-in-law's patent. On the outside, the dolls closely resembled the Huret dolls, and like them, the dolls were fully jointed (108). According to Mme. Porot, the issue in the suit turned on which doll, the Huret or Rohmer, was a jointed doll or poupée articulée (108). Actually, the bodies of the dolls in question were made of different substances; Huret's doll was made of gutta percha, a type of rubber, and the Rohmer/Reidmeister dolls were of stamped metal (108). Yet, Mlle. Huret won the suit (108). It is interesting that the suit did not compare the metal dolls of Huret with those of Rohmer. As a penalty, Maison Rohmer had to pay 100 francs compensation. The dolls that were the subject of the suit were confiscated. Today, a few rare examples survive, and one is pictured in this book, its photo graciously sent by Mme. Porot, the author of the above article. By 1875, Mme. Vuillaume shared a shop with her brother-in-law in the Rue Terrage. By now, M. Reidmeister had taken up again his old occupation of "making horses, velocipedes, and mechanical vehicles for children" (108).

Jumeau, another famous maker of dolls who employed orphan girls in his firm, also used metal parts. Margaret Whitton in Jumeau Dolls shows a spring joint body in the photos on pages 27 and 29. Supposedly, dolls made before and after World War I still used metal springs because rubber for elastic stringing was scarce (Coleman I 113). Some dolls were jointed by copper wires that were twisted onto hooks. The composition bodies used were molded in heavy matrices of steel (Abbot, cited in Johl, MAD, 27). Moreover, Johl claims that one of the younger Jumeau men made fully-jointed bodies with wires inserted into the kid arms and legs that allowed life-like positions (52). Sometimes, Jumeau dolls even wore metal costumes. A large doll called "The Spirit of San Diego" was dressed in a coat of mail. The doll was donated to San Diego by Mrs. Phoebe Hearst, mother of William Randolph Hearst, who built Hearst Castle in San Simeon, CA (Johl, MAD 54). The eyes of Jumeau dolls were attached to a ball of lead before they were inserted into the head (Abbot in Johl, MAD 48). Noted antique expert Robert Reed writes in his article "Love in any Language: the Amazing French Bébé," that the child dolls by Jumeau, Bru, and others, revolutionized the doll world (42). Instead of the French Fashion dolls that nearly always represented women with "bee stung" lips, the new little girl dolls were realistic portrayals of children, approximately eight years old (42). These dolls were noted for the creamy bisque used for their heads, flowing, natural wigs that could be styled, lavish costumes, and hand-blown paper weight eyes. Another innovation was their articulated bodies; the ball joints in these bodies often used metal. In the quest for realism, many of the little girl dolls of the 1880's could perform tasks; Bébé Teteur by Bru nursed from a bottle, Bébé Gourmand ate, Bébé Le Dormeau could close her eyes, the talking Jumeau had a voice box operated by a spring, and another could kiss ( Reed 43).

Bru, the rival of Jumeau, also used kid bodies with metal elbow joints, as did the firm of Daniel and Cie (Fawcett 215). Gesland, another French firm, used the stockinette over metal framework alluded to earlier when foreign dolls were discussed. The heads on these bodies are sometimes marked "F.G." and are attributed to Francois Gautier (Knopf 190). These dolls were often faked, and a large number of them were made in the late 1950's to be sold as old. These, however, were sometimes marked "F + G." One recently appeared on PBS's popular "Antiques Road Show," and it was left to expert Richard Wright to tell a hapless collector that the antique for which she paid a large sum of money was a fake.

Other French heads with kid bodies had metal mechanisms at the base of the head to allow movement (Johl MAD 117). In 1872, a manufacturer named Pannier used metal frames and joints. So did Lucien Vervelle, a man who made metal heads, in 1876. Others who used metal frame for their dolls were Gerardin, for a doll in a cartouche, and Schmetzer, for a dancing doll (White, World, 230). An Emil Robert of Paris took out a patent in 1858 for a doll with metal or wooden limbs. The rest of the doll was to be made of vulcanized rubber (Coleman Marks 89). Moreover, miniature French bisque heads were often attached to the body by means of a metal hook. The author has a three inch example in black bisque with such a hook. The hook attaches to the elastic connecting the doll's arms. Tiny, yellow glass eyes are attached to a mask of plaster inside the doll's head. She wears molded white socks and painted red shoes. The doll is dressed in an outfit of antique lace and red silk. Her black wig is mohair. The firm of Mme. Gesland produced a rare metal body covered in stockinette; the doll's head was made by the firm of Gaultier. Where a woman used a hard, industrial substance like metal for a doll's body, she sought to cover it with a softer material like stockinette, apparently to make it more appealing and to give the body a warmer feel than cold metal. The Gesland doll appears in a calendar by Theriault's Auctions which features antique dolls. Mme. Rohmer also covered her zinc-bodied dolls in Kid.

The so-called Edison phonograph doll had a metal torso in which the phonograph mechanism was inserted. These dolls often had Simon and Halbig heads. (Simon and Halbig was a respected German firm; among the marks it used on its dolls was The Star of David). The Edison Phonograph doll is discussed in more detail in the chapters on automata and mechanical dolls, but it is interesting to note that its body was made of electropated sheet metal. Supposedly, Edison's agents chose Simon and Halbig of Germany to make heads for his doll because they could produce 12,000 heads for $30,000 or about $2.50 each (Formanek-Burnell 45).

Composition dolls, made of a mixture of wood pulp and glue, often had bodies stuffed with straw and hinged with metal discs called "bachelor's buttons." One of these dolls has a poorly painted bisque head and is marked DPC, which is the mark for Dresden Porcelain, Co., Longton (Spinning Wheel 96). Käthe Kruse cloth dolls sometimes have joints reinforced by metal buttons under the cloth (Fawcett 215). More recent examples have wire armatures under their stockinette-covered bodies. Kruse was a German artist who became interested in making dolls because she and her husband believed the bisque dolls made for children were ugly and unsuitable. She advertised her dolls as early as 1911, and hand-painted the realistic muslin faces. The Colemans write in volume two of The Collector's Encyclopedia of Dolls that Kruse probably sued as a model for the dolls a piece of sculpture by Francois Duquesnois (1594-1643) called Francesco Fiammingo (667). Her Husband, Max Kruse, also an artist, supposedly critiqued her dolls and heavily influenced how they were made (667).

Other manufacturers used metal parts in their dolls, some influenced by Kruse and other artists, some not. Doll heads of bisque, composition, celluloid, even plastic, are connected to the bodies through attachments that consist of metal hooks through which elastic or rubber bands are threaded. A famous American doll maker, Madame Alexander of New York City, has used this method for years. The author's Marmee doll of the Little Women series is put together this way. For a student art show, the author drew an exploded view of a Madame Alexander doll, showing the metal hooks and attachments. Bertha Alexander and her sister Rose began making and selling doll clothes in about 1912 (Coleman II 11). By 1926, The Alexander Doll Company was established (11). Bertha continued to run the company until her death in the early 1990s. To this day, the dolls are known for their elaborate costumes. Early dolls were made of cloth or composition, and a few modern, special editions are made of bisque, but most of the dolls are now plastic and vinyl. The story of Madame Alexander parallels and diverges from the stories of Schoenhut and other male immigrants who came to the united states to make dolls. Bertha's father and grandfather had long been involved in doll-making, but the legacy was passed on to the female members of the family. They, in turn, networked and made connections in the same way that male doll makers did, and were successful in an industry that was once a man's world. Also interesting is the fact that Bertha, or "Madame" as she came to be known, made several dolls in her own image, wearing replicas of her trademark pink gowns.

The dolls of Jesse McCutcheon Raleigh were spring strung in a method which also employed metal. Raleigh was born in Indiana in 1881. In 1917, she began making a few dolls and toys, including "The Wise Pig" bank. Her dolls were made of composition and were jointed. They represented either babies or children and had painted or sleeping eyes (Whitton in Doll Reader Magazine, 78-79). Also, the Raleigh company made a series of figurines called "The Good Fairy" which were cast in different materials, including silver and bronze. Similar to these are pewter figures created by a company called Memories in Pewter.

Grace Bliss Stewart, another woman doll making entrepreneur, designed the Good Fairy figurines for Raleigh. Artist Josephine Kerm modeled it. Italian workmen were then hired to make molds. Then, the good Fairy was cast. These figurines stand about ten inches with a base twelve inches in circumference. They were very popular and there were "Good Fairy" clubs all over the world. Helen Keller, who loved dolls and figurines from childhood, owned one of the Good Fairies, and said of it, "I feel its smile like a sunbeam in my darkness" (78).

Another famous and unusual composition doll of this period that had tin eyes was the "Fly-Lo" Baby created by Grace Storey Putnam (Anderton 118). Putnam had great success with another doll, the Bye-Lo baby, modelled after a three day old infant. After four, desperate years of trying to market the doll herself, Putnam approached George Borgfeldt (Coleman II 966). The doll became an overnight success during the mid 1920s and made Putnam a wealthy woman. Putnam's story is remarkable because, unlike some of the other doll makers mentioned, including Bertha Alexander, she had not knowledge of the doll making industry, no contacts, and no commercial experience. Her own creativity and persistence paid off.

Celluloid dolls could also have metal parts. Alexander Parkes (1813-1890) is credited with inventing celluloid, originally called Parkesine (Percy Reboul in Ward 9). Celluloid is a type of nitrated cellulose that can closely resemble ivory, but is much more durable. The Minerva Doll Company made celluloid as well as metal ones. Companies in France, England, Japan, and the United States did the same. Celluloid dolls often employed metal parts in their make-up, too. One of these was the Parsons-Jackson baby, whose joints were held together by wire springs (White, World, 231).

Talking dolls and mamma dolls from the nineteenth century on had metal voice boxes implanted in their bodies. From 1923-27, many doll's voices were made by the Art Metal Works (Coleman 1010). One doll in the author's collection, the size of a two-year old child, even has a phonograph mechanism implanted in its body. When one turns the handle, the doll plays music.

Many walking dolls have metal knee joints, and, in some examples, metal torsos. One of these is the Nunn walking doll. The patent for this doll was taken out on November 15, 1922, No. 186,232. The doll had metal spring hinges at the knee joints on legs attached with pivot joints so that they moved freely with the body. Supposedly, Queen Mary admired these dolls at the Wimbley Exhibition held in London in 1924 (Spinning Wheel 197).

Kewpie dolls, inspired by Cupid and designed by illustrator Rose O'Neill of Branson, Missouri, were made in metal molds or had metal parts. Formanek-Brunell in Made to Play House calls O'Neill "an internationally recognized artist, writer, and Greenwich Village Bohemian" (117). Kewpies first appeared in women's magazines in 1909, in materials ranging from "china to chocolate" (117). By World War I, Formanek-Brunell claims that the Kewpies were the most popular characters "in American popular culture until Mickey Mouse" (117). Rowena Ruggles, most famous biographer of O'Neill, tells of a metal master mold in the collection of a woman from Downers Grove, Illinois. This mold once belonged to Joseph Kallus, who sculpted the Kewpies in vinyl for the Cameo Doll Company (Ruggles 28-30). The author recently saw a mold for a three inch Kewpie at a doll show near Chicago. Kewpies were also cast in gold or silver for jewelry (30). California artist Morgan Fisher made silver Kewpie earrings ten years ago. Heavy cast metal banks representing Kewpies and metal candy molds have also been found in collections.

Manufacturer like O'Neill shared a child-centered agenda according to Fromanek-Burnell (118). They were not, like their male counterparts, only interested in the process. O'Neill and other women designing dolls felt "freed from tradition and convention" (118). O'Neill created her dolls from drawings and original representation of children (118). Many modern doll makers like Annette Himstedt, whose elaborate vinyl dolls employ metal in their joints, follow her lead and create dolls from sketches drawn of real children. The Kewpies were more than portraits of infants, however. They were totally unfettered spirits, and had wings (118). O'Neill's new ideas about gender influenced modern trends in Kewpie cartoons. The Kewpies were comfortable wearing no clothing, or representing Suffragettes (118). Kewpies "mothered" orphans (119), but also represented contemporary politics. One Kewpie even wears a Kaiser helmet. Formanek-Brunell argues, though, that male manufacturers, once they had her designs, changed O'Neill's vision, so that Kewpie dolls, meant to be androgynous, began to be dressed like little girls.

Other novelty dolls, similar to the Kewpies, that employ metal parts are dolls made for holidays such as Halloween and Christmas. Many angels made in Germany or Japan during the forties and fifties have metal halos and metal wings. Some have heads made of glass mercury balls dipped in metallic paint. Even doll ornaments of blown glass, like those by Christopher Radko, are blown with the use of metal rods.

After Christmas, most agree that the most decorated holiday is Halloween. Many Halloween character dolls of the 1920's had parts made of metal. An unusual example is a jack-o'lantern windup clown, circa 1920. This doll has a cardboard, or papier maché type head painted like a grinning pumpkin. He has metal legs and feet, and wears an orange clown suit, with orange pompons, a green ruffle at the neck, and an orange and green clown hat. So rare is this doll, especially in good condition, that it recently fetched $2100 at auction (Wenzel 45). Another windup pumpkin clown wears a white ruffle, and green Leder Hosen, as if he were from Germany or Switzerland. He, too, has metal parts in his mechanism, and is rare. He also dates from 1920 (Wenzel 44). More mechanical holiday dolls are discussed in the automata chapters and in the chapter on modern dolls.

Largely because of its durability and flexibility, metal became a popular material to use for making doll parts. Certainly, doll makers of both genders had an interest in providing products that were versatile and would withstand rough childplay. Yet, perhaps Formanek-Brunell and others have a point that male doll makers chose metal and other hard substances because these materials provided an "outlet for the skills the inventors themselves possessed" (45).

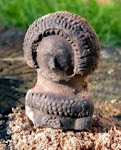

88. Left to Right: Cast iron figural bank, replica of early twentieth century piece, 8 inches. Iron Asian incense burner, lid to box opens. 1920s. (Author's collection).

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

wCWk~%24(KGrHqV,!h8Ew5GsnS3dBMUy3MzVPg~~_3.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment